The One Thing My Father Told Me Never to Do

Sometimes the thing you avoid is the thing you were always going to do anyway.

When I was 17, my dad pulled me aside and told me exactly what NOT to do with my life.

You have to understand something about my father. This was a man who defused bombs in World War II. He parented largely through passive aggression and well-timed looks. He almost never told me anything about how to live my life.

So when he looked me dead in the eye and said, “Son, you can be anything you want to be in this life. You have the skill, passion, and drive to do anything you want,” I leaned in.

Then he paused.

“Don’t be a teacher.”

My dad was a teacher. My mom was a teacher. My brother was a teacher. And in time, my sister became one too. I grew up in a house so full of educators that our dinner table basically had office hours.

And here was the patriarch of that household, a man who survived disarming live ordnance, telling me with all the earnestness he could muster not to follow in his footsteps.

So yeah. I went a different way.

I went into restaurants. Which (oddly) led to Kinko’s. Which led to desktop publishing. Which led to Adobe. Then a startup. And an entire life in tech.

And now? Well, I’m teaching at North Seattle College. Running online workshops. Working with companies on AI readiness. And writing this newsletter about simplifying the stuff that feels overwhelming, which, if we’re being honest, is just teaching with better fonts.

I don’t know if Dad would be proud or mortified.

So this week, let’s talk about the things we can’t outrun, why the long way around isn’t wasted, and how to recognize when you’ve been doing the thing all along.

You’re Soaking in It

Psychologist Albert Bandura spent decades studying how people learn. What he landed on, Social Learning Theory, boils down to something every parent already knows: your kids are always watching.

The theory says we don’t just learn from direct instruction or personal experience. We learn by observing the people around us, absorbing their behaviors, attitudes, and reactions, then reproducing them as our own. Bandura called it observational learning. And the people we observe most closely are the ones with status, authority, and proximity. Like Mom and Dad. Every single day.

Researchers studying career patterns found that children of military parents were nearly four times more likely to go into the military. Kids of farmers became farmers. And children of teachers? You can see where I’m going with this.

Of course, I didn’t know any of this as a pimply-faced 17-year-old. All I knew was that our house ran on lesson plans, red pens, and the unmistakable exhaustion of people who cared deeply about other people’s kids as well as their own. I watched my parents grade papers at the kitchen table. I saw the frustration when a student wasn’t getting it, and the quiet pride when one finally did.

I was absorbing a masterclass in teaching.

Bandura would say all four stages of observational learning were ticking away in the background. Attention. Retention. Reproduction. Motivation. Like a clock I couldn’t hear, but still recording the time.

And that’s the tricky thing about what you grow up around. You don’t have to chase it for it to get inside you. It just moves in. Sets up shop. Waits.

My parents never once told me I should teach. My dad actively told me not to. But the modeling was already done. I’d spent nearly two decades watching people translate complicated ideas into simpler ones. Watching them connect with struggling learners. Pounding knowledge into (at times) idle brains.

Especially mine.

In middle school, dad threatened to ground me for mixing up “their” and “there” in a paper. He might have been kidding. Was he kidding? I honestly don’t know and I have had that locked in ever since.

That wasn’t a career track. It was a worldview. And worldviews don’t care about career plans.

Oh hey, quick aside: If you’re getting value from this newsletter and want to support what I’m building, consider upgrading to a paid subscription. You’ll get a monthly digital goodie boxes, stickers (yes, actual stickers), and the satisfaction of knowing you helped fund my questionable police car choices.

The Forbidden Fruit Is Always Sweeter

Ever hear of Reactance Theory? No? You didn’t know you’d signed up for Psych 101 with this newsletter, did you? Oh yeah, mom also taught Psychology.

In 1966, psychologist Jack Brehm coined the term to describe something we’ve all felt. When people sense their freedom of choice is being restricted, they experience a motivational state aimed at reclaiming that freedom. Put simply: tell someone they can’t do something, and they suddenly want to do it more.

Brehm ran experiments with toddlers. He put toys behind barriers of different heights. The toys behind the tall barriers, the ones that were harder to reach, were consistently the ones the kids wanted most. The toys were identical. The only difference was that one group was told, in effect, “no, not that one.”

Now, I’m not saying my dad’s advice backfired in any obvious way. I didn’t storm off at 17 to get a teaching certificate out of spite. I genuinely went a different direction. Restaurants, copy shops, tech. Thirty years of a different direction.

But Brehm’s research points to something subtler than outright rebellion. Reactance doesn’t always show up as defiance. Sometimes it shows up as a quiet gravitational pull. A thing you can’t quite name that keeps nudging you toward the door marked “DO NOT ENTER.”

My dad told me not to teach. And for decades, I didn’t. But the whole time, I was doing something suspiciously close. Translating complicated tech jargon into language normal humans could understand. Running workshops. Writing things that helped people figure stuff out. I tell people I speak three languages: English, Engineer, and Customer.

That’s teaching. I was just calling it something else.

Which makes me wonder how many of us are doing exactly that. Running from a thing while accidentally running toward it. Changing the label on the jar without changing what’s inside.

Reactance doesn’t always look like rebellion. Sometimes it’s quieter than that. The pull doesn’t go away just because you ignore it. It just gets patient.

The Scenic Route Has Better Views

Here’s where I could tell you that I wasted three decades avoiding my true calling. It would make for a tidy narrative. The prodigal teacher, returning home after years in the wilderness.

But that’s not quite right. Teaching isn’t my whole life now. It’s a part of it. I still do consulting. I still work in tech. But I teach a class at North Seattle College on the side and run online workshops about making sense of AI (shameless plug!) The teaching piece isn’t a replacement for everything else. It’s more like the thread that finally ties everything else together.

And that thread only exists because of the detours. But those detours aren’t detours at all. They’re prerequisites.

My years in restaurants taught me how to read a room and talk to people. Kinko’s taught me patience and introduced me to technology. Adobe gave me a front-row seat to how technology reshapes entire industries. A startup taught me how to build things from scratch and figure out how to make them work for real, actual people.

Every single one of those jobs was secretly building the skill set I use now.

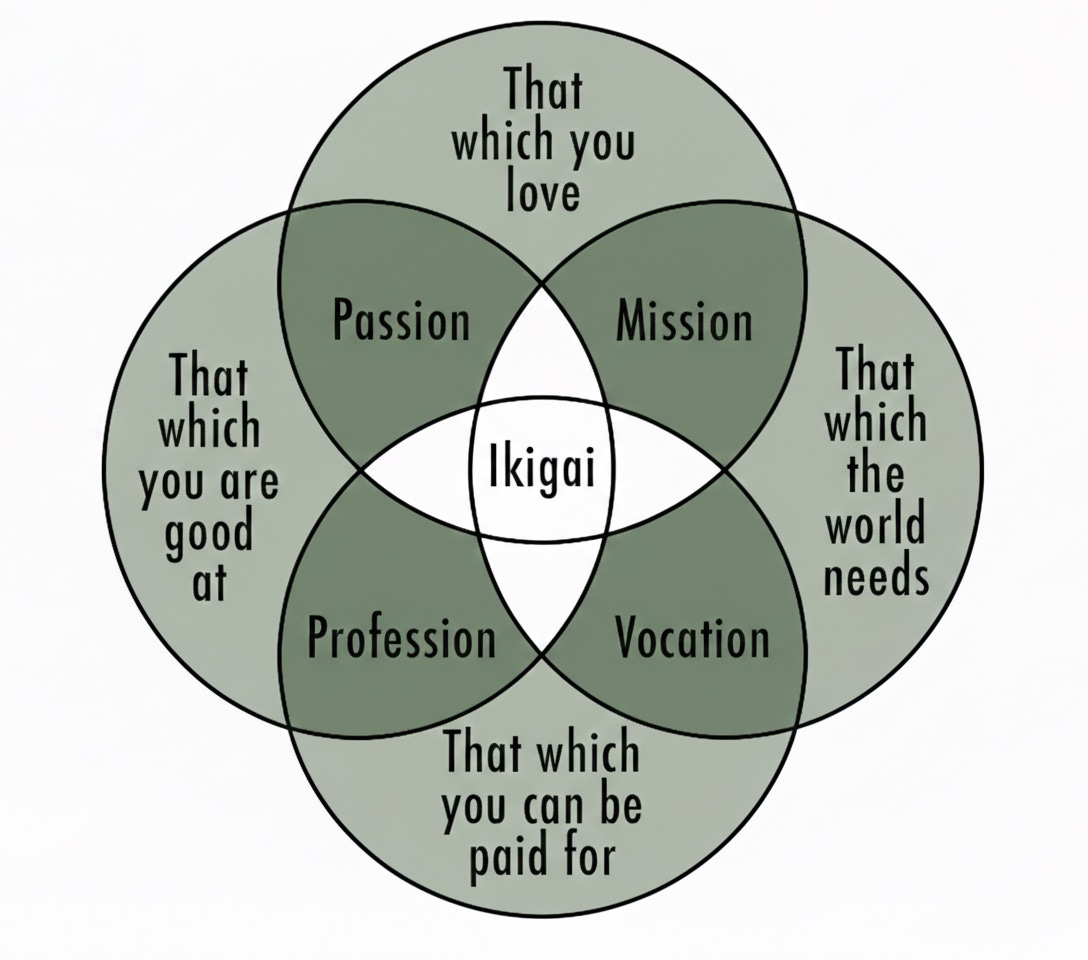

Which brings me to a Japanese concept called ikigai. It translates roughly to “a reason for being,” and it’s often shown as four overlapping circles: what you love, what you’re good at, what the world needs, and what you can be paid for. Where all four overlap? That’s your ikigai. Your sweet spot.

Most of us don’t land there in a straight line. We find one circle at a time. You spend years doing what you can get paid for. You stumble into what you’re good at. Somewhere along the way, you notice what you love. And if you’re lucky, you realize the world actually needs it too.

The scenic route isn’t wasted. It’s how you fill in the circles. (And ikigai is something I’ll be writing a lot more about in a future newsletter. Stay tuned.)

So if you’ve been wondering whether your own winding path is leading anywhere, here are a few questions worth sitting with:

What keeps showing up? Look across your jobs, hobbies, and the things people ask you for help with. Is there a thread? For me it was always simplifying the complicated. Didn’t matter if it was a restaurant menu, a copy machine, or an AI platform.

What do people say you’re good at that you never trained for? That’s probably something you absorbed, not studied. The thing that feels effortless to you but valuable to everyone else.

What are you doing for free that other people charge for? If you keep doing the thing without getting paid, that’s not a hobby. That’s a circle waiting to overlap.

What did you grow up watching? Go back to Bandura. The behaviors you observed as a kid didn’t disappear. They’re still running in the background. What did the adults in your life do every day that you now find yourself doing too?

You don’t have to blow up your life. You don’t need a grand pivot. But if you’ve been circling the same thing for years, calling it different names in different contexts, maybe it’s time to stop and call it what it is.

The long way around isn’t wasted after all. And might just be thing you’ve been doing all along.

In Conclusion

I never asked him why.

Why teaching was the one thing to avoid. He never said and I never asked. I can guess it had something to do with the poor pay, the lack of appreciation, the mountain of grading and prep. But those are me filling in blanks he left empty.

That conversation was a long time ago. But only if you measure in terms of years.

My dad told me not to follow in his footsteps. And I listened for a few decades. But when you tell someone not to do something that's already in their DNA, you don't kill the impulse, you kinda just buy them time. Time to go out, gather experience, and come back to it on their own terms.

So yeah, I'm teaching. And I don't think he'd be surprised.

I was always a great student, but I can be a terrible listener.

Ever forward,

— Derek (aka Chief Rabbit)

P.S. Dad wouldn’t like it but I'm teaching a beginner-friendly AI workshop online. No prior experience needed. Just curiosity and a willingness to try something new.

Here is a relevant anecdote, perhaps. Neither of my parents were teachers, but I grew up loving school as the complex universe of opportunity that it is. My favorite area was history, so by the time college was looming, I was set on becoming a high school history teacher. But then....

Our high school had an elective program where you served as a teacher's assistant in a nearby elementary school. Not a great match, sure, but it would give me experience in a "teaching" setting. Spent a semester in fifth grade (forgettable) and then a semester in second grade (epiphany.) Switched to primary for my college training, and started my career with eight years in third grade. Moved up to sixth for the next thirty, half in elementary and then half in middle school, where I did actually specialize in social studies. So the scenic route never quite reached full circle, but it was quite a journey.

Love the graphic and the lesson...Thanks, Derek